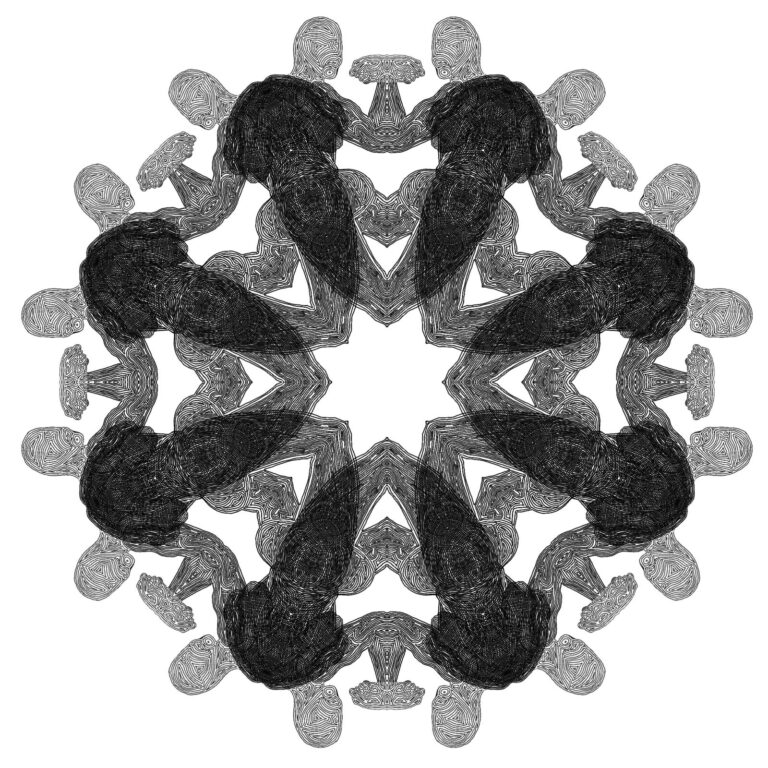

Rohingya Youth Association (Credit: Khin Maung)

In Cox’s Bazar Bangladesh, a group of young Rohingyas have organised a free blood diagnosis campaign in the camp. The slogan is ‘Your health and wellbeing are our responsibility’.

One after the other learn how to correctly poke the thin fingers of the scores of children in the camp for the blood tests. There is a common expression on their faces, a look of hope. “Before this, we’d been happy if we lived for another five years,” says 27-year-old Khin Maung.

A couple of years ago Maung created the Rohingya Youth Association, a network of young Rohingyas from around the camps in Bangladesh. Since then, he has engaged hundreds of youths in professional courses like health education.

With the scarce resources in the refugee camps, teenagers who never stepped foot outside the camps to go to school are learning about health for the first time. “I wanted to create a purpose for us. To want to wake up every morning and achieve something,” Khin Maung says.

Khin Maung was only a teen when he left his home in Myanmar- formerly known as Burma. He has witnessed years of violence at the hands of military forces, branded by the UN as systematic ethnic cleansing.

Bangladeshi authorities closed all schools inside the camps, arguing the Rohingya community leaders failed to secure permission to open them. The country has, however, granted permission to UNICEF and other agencies to operate schools for younger children in the camps.

“Life in the camps is frozen. No education. No jobs. We grow up without wanting to have a tomorrow,” says Khin Maung.

He is one of more than a million Rohingya who are currently living in squalid camps in southern Bangladesh, Cox’s Bazar. They represent the world’s largest refugee settlement, with the vast majority having fled from Myanmar during a military crackdown in 2017.

Almost six years on, the Rohingya people are still hanging in legal limbo as one of the largest stateless communities. The UN has recently cut food aid to Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh.

According to UN Special Rapporteurs, the decision will result in a spike in malnutrition in a community in which more than half of Rohingya children are affected by stunted growth.

“Cutting humanitarian aid is pushing young Rohingyas to be at the mercy of human traffickers and risk their lives for a better future,” says the Director of the Free Rohingya Association, Tun Khin.

“As Rohingyas, this is very devastating. Their only way to survive is escaping. Human traffickers are misusing the desperation of hundreds of women and children,” he says.

Rohingyas are trapped in a state of uncertainty. Rejected by the nation they called home, they embark on deadly routes to find a welcoming country. Recent UN reports show that more than 3,500 Rohingya refugees risked their lives to flee Bangladesh or Myanmar in the last year.

Khin Maung has been campaigning online to raise funds to pay for laptops and whiteboards for his courses. In the last year, he has raised thousands from charity organisations and Rohingya donors from the diaspora. “If we don’t work for our future, no one will. Without a purpose we are futureless,” he says.

“In Burma, there is no future. Young women tell me, ‘I have no brother, no father, they all got killed in Burma, the only way out is escaping to another country through boats,” says Khin Maung.

“I don’t want to see the future of young Rohingyas end in the sea. I have the responsibility to save the next generation,” he says.