Credits: Yadira Piaguage

When he was a child Justino Piaguage used to cross the river Wa’iya with his friends to get drinking water and to swim in the mighty River Aguarico. One day he realised that something had changed. The waters turned black. “I saw a black thick substance coming out from the land,” says Justino. The river was contaminated with fuel oil. “I thought the land was bleeding black blood.”

Since then, black stains in the soil have become the new landscape for the Siekopai indigenous community. The polluted river is the consequence of the activity by the North American oil company Chevron-Texaco which has been exploiting the land of indigenous groups for over 20 years.

‘It’s painful to watch the Amazon bleed before our eyes’

Justino Piaguage leader of the Siekopai people

As President of the Siekopai Original Nation, Justino Piaguage has continually tried to sue the transnational oil producers to remove the gas flaring and take responsibility for the disastrous consequences to his land.

“I was the youngest person to sign the complaint. I couldn’t keep watching my parents suffer because of all the injustice they have seen. It was painful to watch the Amazon bleed before our eyes and not be able to do anything,” he says.

Resistance runs in the family. Like many other young Siekopai, Justino’s daughter Consuelo Piaguage, now 26, grew up amid the polluted rivers and black mud. “My shoes were always covered in black because we used to walk and play in oil puddles,” she says. “I don’t know what it is to live happily in the Amazon. All I know is the sound of the excavators and the smell of petrol.”

Consuelo witnessed her grandparents pass away from cancer. Growing up she had never seen a clean rainforest. All she remembers is the word Chevron.

“We would always carry a plastic bottle filled with boiling water. We were banned from drinking from the rivers. My dad would say we were too young to die,” she says.

Oil spillage in the Conejo River, Province of Sucumbios, Ecuador.

Chevron admitted to having dumped over 18.5 billion gallons of toxic water into the rainforest when it first started to operate in the early 2000s. That is about 4 million gallons daily contaminating 2 million acres of the Ecuadorian Amazon.

In 2011 the Ecuadorian High Court ruled that the company had to pay compensation of $9.5bn (£7.6bn) to the affected communities. However, more than a decade on, the victims have not received a single penny and their lives have been impacted forever.

A study conducted by the organisation for the victims of the Chevron disaster UDAPT and Environmental Clinic found 442 cases of cancer between 2018 and 2022 in oil-producing areas of the Amazon. Of those cases, over 72 per cent were women.

‘All I know is the sound of the excavators and the smell of petrol’

Consuelo Piaguage giving a speech in a cultural centre.

“This ecocide has marked our generations. We are a sick nation drinking dirty water and breathing polluted air,” says Justino.

In 2014 a company called PetroAmazonas conducted a gas exploration next to Consuelo’s home in the Sucumbios Province in search of oil. According to Consuelo, her father Justino negotiated compensation in the form of university scholarships for the young people in the community.

“I was the first one in my community to go to university, but at the cost of my family’s land,” Consuelo says.

This year, Consuelo attended the Confederation of the Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuadorian Amazon (CONFENIAE) in Peru to talk about the Siekopai’s resistance to the oil industry. “Our fight is part of a larger movement of Amazonian nations. We are all up against the same enemy,” she says.

“I grew up seeing my dad fighting for our survival. I must do the same. I don’t want my children to die not knowing where they came from,” she says.

‘We want to say to the world that we are alive’

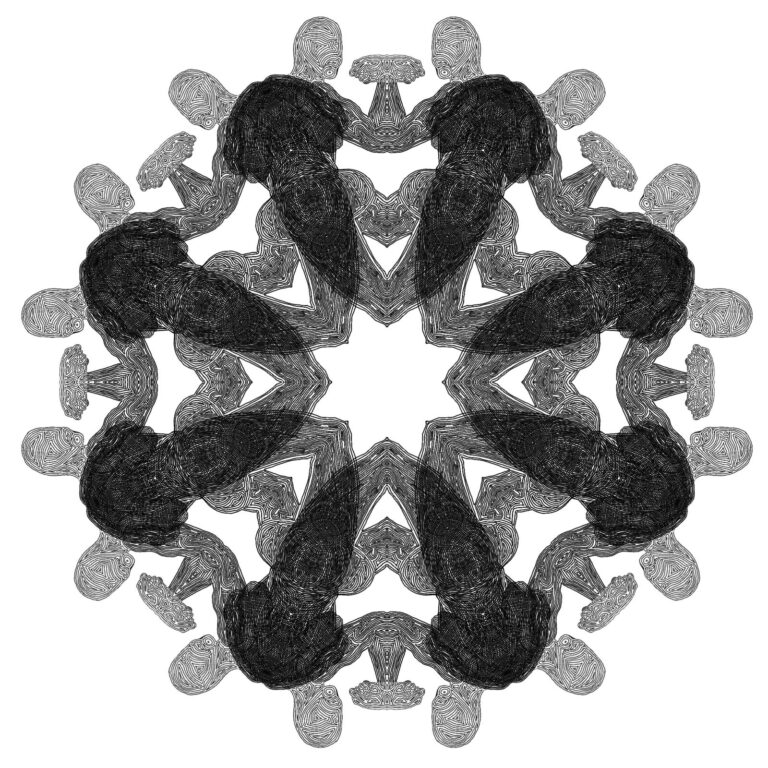

Yadira Ocoguaje teaches other women from her community the ancient tradition of ceramics

Consuelo’s childhood friend Yadira Ocoguage, 27, is fighting on a different front. Every week she walks miles to collect clay from the rivers. “Soto-Ya, Soto-Ya, I seek your permission to take your clay,” she sings to the goddess, just like her grandmother used to do. She is reviving the ancient art of ceramics of the Siekopai people.

From the rolling technique of the clay to the walls of the pot, she teaches the women of her community step by step. Short lengths of coil are added to build a cup that will be used for cooking. She then paints it to create distinctive figures – a snake, a butterfly, or a bird.

“The figures represent us. The water, earth, and the union of Siekopai women,” she says. “Through the shapes and colours, we reflect our feelings. Ceramics are a mirror of who we are,” she explains.

Ocoguage teaches the sacred art of ceramics through workshops and women’s reunions at her house and in local schools. For her, clay is more than a term, it is a means of reviving an intimate part of the Siekopai culture.

“I’ve been doing it since I was a little girl. My grandma taught me before she passed. I’m keeping alive her legacy through it,” she says.

But in the province of Sucumbios, clay is scarce. Decades of pollution and deforestation have gouged the valuable Licania Capetalia – the tropical plant used for mixing with the clay to make it heat resistant.

Ocoguage is creating a means of financial income for other women by organising stalls around the country to sell her pottery. She aims to teach women from all around the province of Sucumbios the dying craft. “I started teaching my sisters and then more women joined. We all wanted to keep our grandmother’s legacy alive,” she says.

We are raising our voices,” she says. “Through ceramics, we can say to the world that we are alive. We are more than just a land to be exploited.” Yadira Piaguage

‘Our displacement is worse than death. We risk being forgotten as if we never existed’

The Amazon tropical forest extends to over 2.86 million square miles, nearly the size of the land area of the US. The greenery covers about five per cent of the Earth.

The Siekopai are one of 400 or so distinct indigenous peoples in the Amazon serving one cause – stopping their own disappearance.

Also Read: Change starts with me: young people campaign against plastics for World Ocean Day

The insecurity and lack of basic resources for survival in the community are causing an unprecedented exodus from the rural areas to the city. According to experts, the destruction of the Amazon will be irreversible in the next 30 years.

“Our displacement is worse than death. More and more indigenous people are escaping to the cities. If we leave our ancestral land and lifestyle behind, we risk being forgotten as if we never existed,” says Justino.

“The Amazon is the lung of the earth. It is the soul, the latent heart. We need to look at the Amazon with human eyes and not with those of capitalism.”